Not everything I read makes it here, but the ones that do were worth writing about.

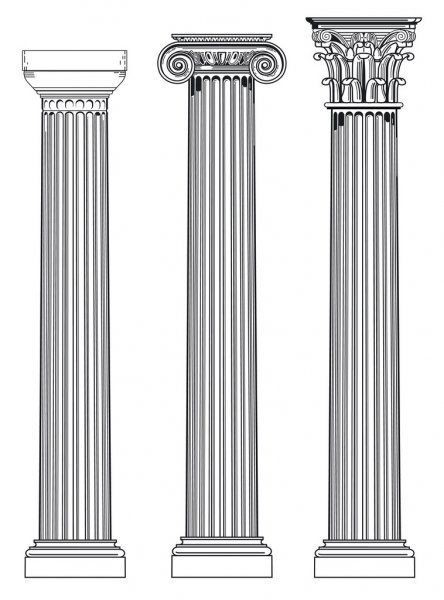

Symposium

PlatoI often think of Plato's writing as essential reading—even for a 21st-century human. I'm always tempted to tell my friends to read more philosophy, because its impact is far more practical than people expect. We're accelerating into a world where questions about consciousness, peaceful living, love and sex, and what "success" even means are becoming central again.

I often think of Plato's writing as essential reading—even for a 21st-century human. I'm always tempted to tell my friends to read more philosophy, because its impact is far more practical than people expect. We're accelerating into a world where questions about consciousness, peaceful living, love and sex, and what "success" even means are becoming central again.

Plato's Symposium is a perfect example: an unexpectedly practical device for thinking about love and relationships. In a lively, conversational debate—set at a drinking party—Plato shows how the ancient Greeks made philosophy a social sport: something you argued about with friends, out loud, in real time.

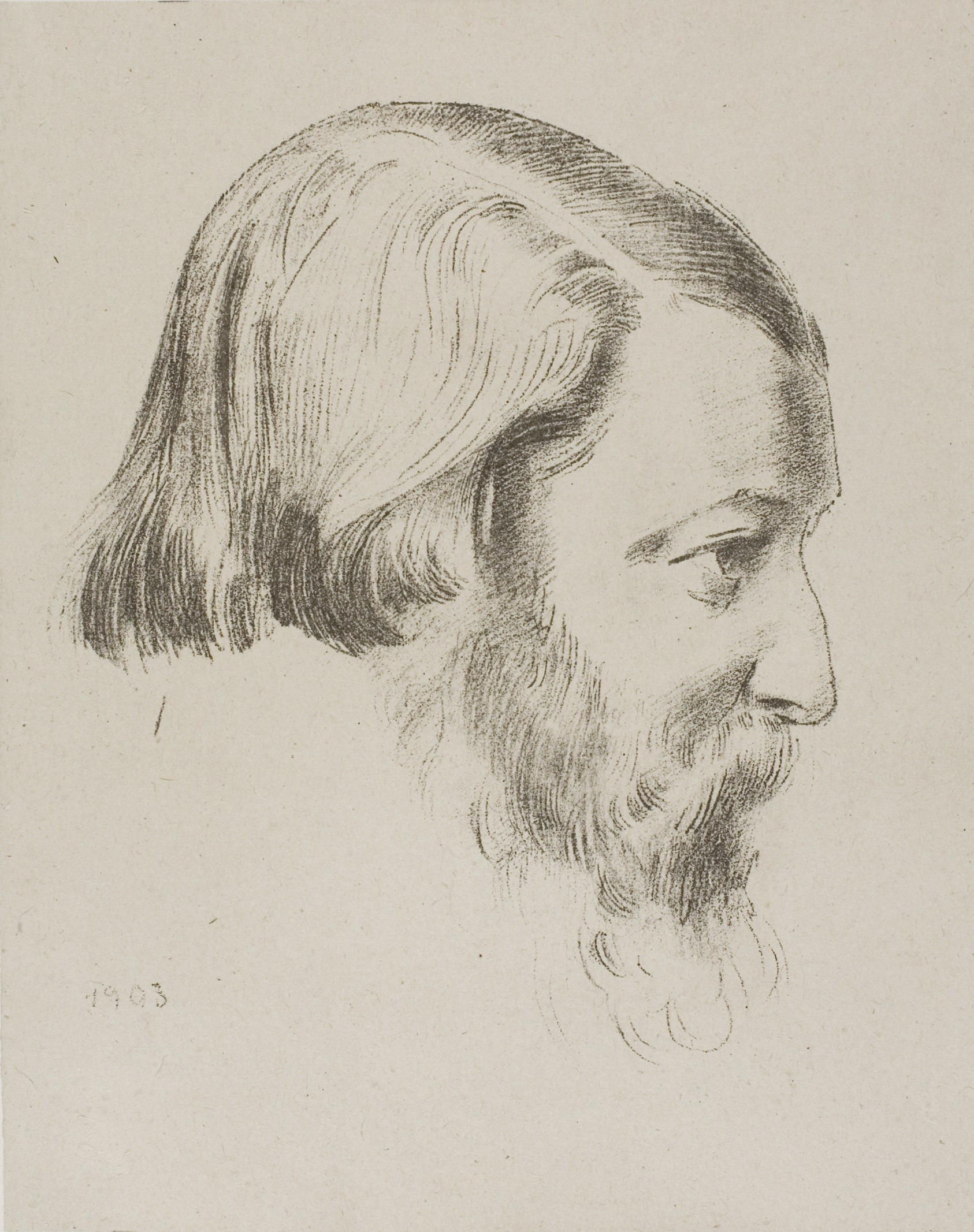

Crime and Punishment

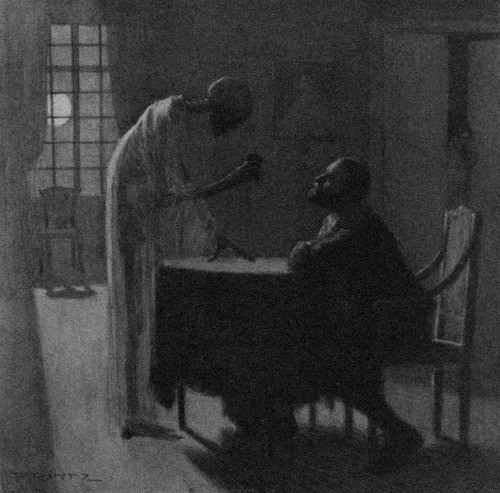

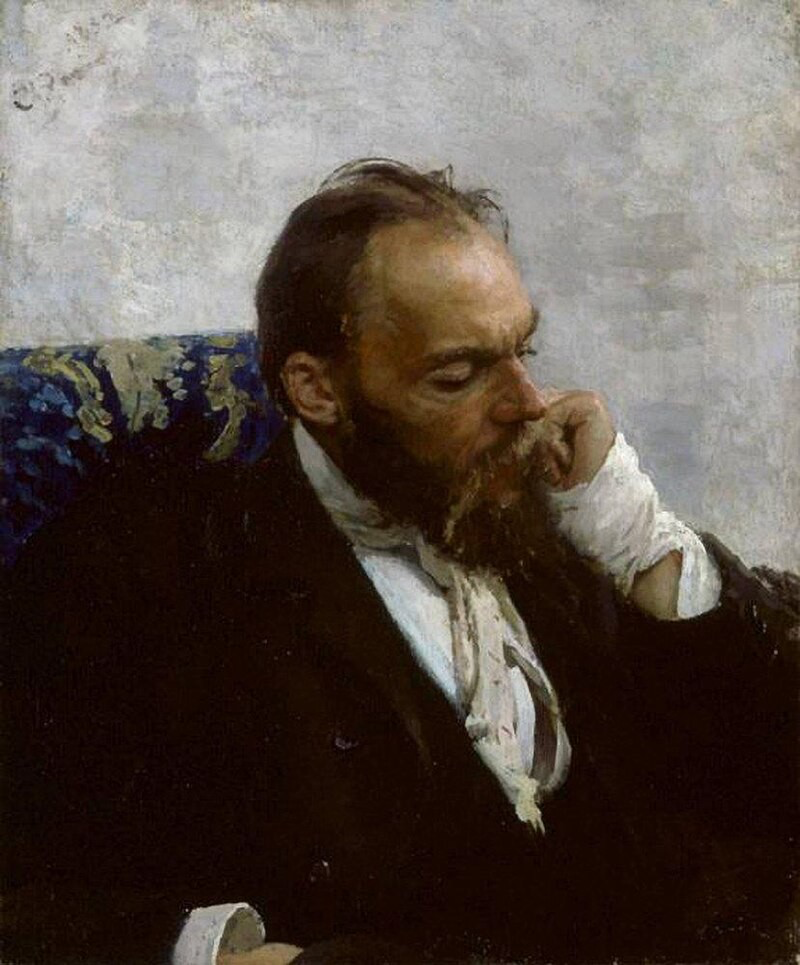

Fyodor DostoyevskyCrime and Punishment is one of the most psychologically intense books I've ever read—not because of the crime itself, but because Dostoyevsky makes you live inside the aftershock. It's a novel about conscience as a physical force: the way guilt changes your sleep, your body, your relationships, your sense of time.

Crime and Punishment is one of the most psychologically intense books I've ever read—not because of the crime itself, but because Dostoyevsky makes you live inside the aftershock. It's a novel about conscience as a physical force: the way guilt changes your sleep, your body, your relationships, your sense of time. You're watching a mind try to rationalize the irrational, to defend a theory of "special people" while quietly being dismantled by the very humanity it tried to outgrow.

What makes it timeless is that it isn't really about law—it's about self-judgment. The punishment isn't only external; it's internal, spiritual, and social: isolation, pride, delirium, the inability to accept love. And yet, the book isn't just bleak. Beneath the suffering is a hard-won argument for humility and for redemption that comes through truth—confession, responsibility, and finally letting yourself be seen. It's exhausting in the best way: a book that doesn't let you stay superficial about morality, or about what it costs to betray your own soul.

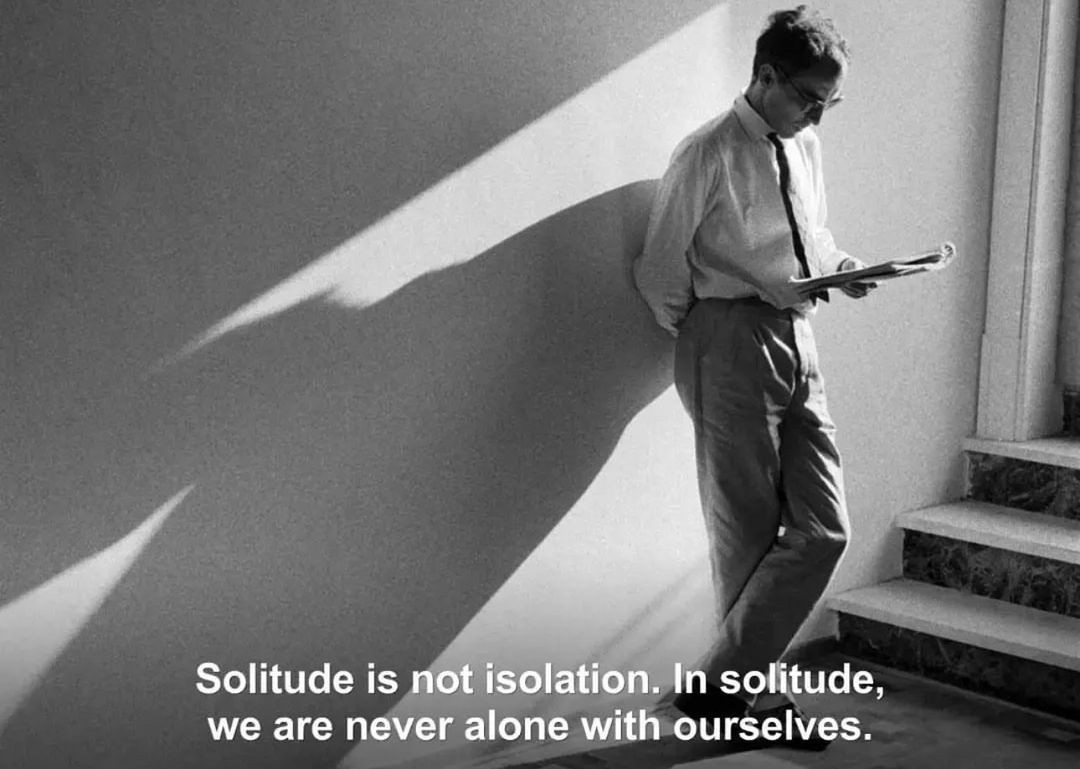

Letters to a Young Poet

Rainer Maria RilkeIf someone put a gun to my head and asked what my favourite reading of all time was — it would be Rainer Maria Rilke's masterpiece, Letters to a Young Poet. It's the rare kind of writing that feels like it was meant to find you at exactly the right moment: not advice in the usual sense, but a steady hand on your shoulder when you're anxious about talent, purpose, love, and whether you're "doing life" correctly.

If someone put a gun to my head and asked what my favourite reading of all time was — it would be Rainer Maria Rilke's masterpiece, Letters to a Young Poet. It's the rare kind of writing that feels like it was meant to find you at exactly the right moment: not advice in the usual sense, but a steady hand on your shoulder when you're anxious about talent, purpose, love, and whether you're "doing life" correctly.

What makes it unforgettable is how gently it refuses shortcuts. Rilke doesn't tell you how to become great—he tells you how to become honest: to turn inward, to be patient with uncertainty, to stop outsourcing your standards to applause, and to treat solitude not as a flaw but as a forge. Every reread changes depending on where I am in life, but the effect is always the same: it quiets the noise and points me back toward the only thing that actually lasts—doing the work, living the questions, and becoming someone whose life can hold the answers.

The Prince

Niccolò MachiavelliAlthough Machiavelli failed to save the Florentine Republic, his lessons have stubbornly outlived the moment that produced them. The Prince is the root system of what we now call political strategy—power, incentives, optics, coalition-building, and the uncomfortable gap between how we wish people behaved and how they often do.

Although Machiavelli failed to save the Florentine Republic, his lessons have stubbornly outlived the moment that produced them. The Prince is the root system of what we now call political strategy—power, incentives, optics, coalition-building, and the uncomfortable gap between how we wish people behaved and how they often do. Reading it felt like discovering the original blueprint for "getting an edge": not in a cartoon-villain way, but in a cold, analytical way that forces you to see reality clearly before you try to change it.

The context makes it even sharper. After the Medici returned to power, Machiavelli was pushed out of office, accused of conspiracy, imprisoned, and tortured (the strappado) before being released. Banished from public life, he retreated to his small farm at Sant'Andrea in Percussina, where he poured his frustration into writing—most famously drafting The Prince in 1513 as both a diagnosis of power and a bid to re-enter political relevance. And he didn't only write grim political theory in exile: he also wrote satirical comedy—La Mandragola (The Mandrake), likely composed around 1518—proof that the same mind that dissected rulers could also skewer human weakness with humor.

One small correction that surprised me too: the root of "manage/management" traces back to Italian maneggiare (to handle—originally, to handle/train horses), rather than a Machiavellian coinage. That feels fitting anyway: the book is, in many ways, about the dangerous art of handling power—without letting it handle you.

The Kite Runner

Khaled HosseiniThe Kite Runner is one of those books that leaves a permanent mark—because it doesn't just tell a story, it changes the emotional vocabulary you use to think about guilt, loyalty, and redemption. It's intimate and devastating, but also deeply human in the way it shows how a single moment can echo across an entire life, and how "growing up" sometimes means finally facing the thing you've been running from.

The Kite Runner is one of those books that leaves a permanent mark—because it doesn't just tell a story, it changes the emotional vocabulary you use to think about guilt, loyalty, and redemption. It's intimate and devastating, but also deeply human in the way it shows how a single moment can echo across an entire life, and how "growing up" sometimes means finally facing the thing you've been running from.

And Baba's line is still stuck with me: "There is only one sin, only one, and that is theft. Every other sin is a variation of theft." It's a brutal moral compression, but it works—it forces you to see harm as taking: taking trust, taking dignity, taking innocence, taking time you can never return. This book made me think about the cost of silence and the weight of cowardice, but also about the strange, hopeful possibility that redemption can be real—if you're willing to tell the truth and pay what it costs.

The Little Prince

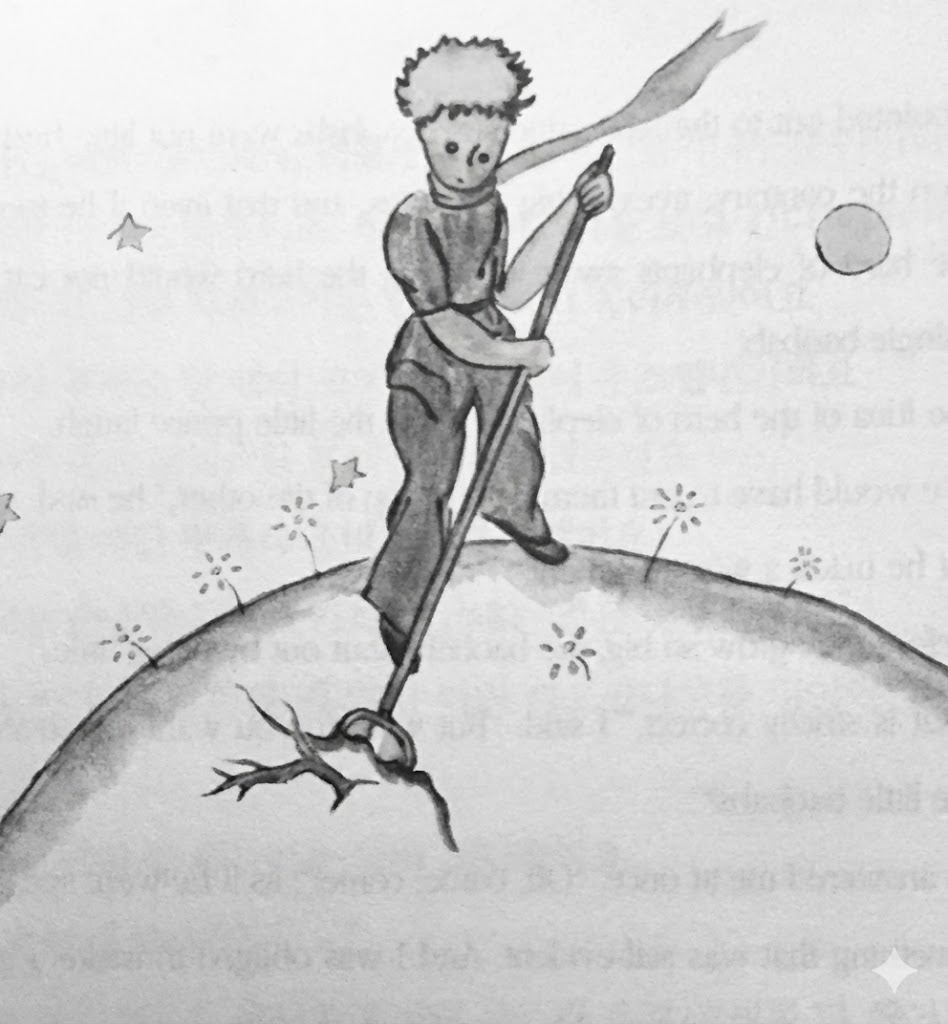

Antoine de Saint-ExupéryThe Little Prince is one of those rare books that stays simple on the surface and somehow gets deeper every time you return to it. I adore it because it's gentle without being naïve: it talks about love, loneliness, responsibility, and meaning in a way that slips past your defenses.

The Little Prince is one of those rare books that stays simple on the surface and somehow gets deeper every time you return to it. I adore it because it's gentle without being naïve: it talks about love, loneliness, responsibility, and meaning in a way that slips past your defenses. Each reread feels like meeting a different version of yourself—sometimes I notice the humor and absurdity of "grown-up" priorities, other times I feel the ache of distance, grief, or devotion underneath the story.

What I take from it, again and again, is the reminder that what matters most isn't loud or measurable. The book makes you look at attention as a form of love, and responsibility as something chosen—not imposed. It's short, poetic, and quietly devastating in the best way: a reset for how to see people, and how to live.

Liar's Poker

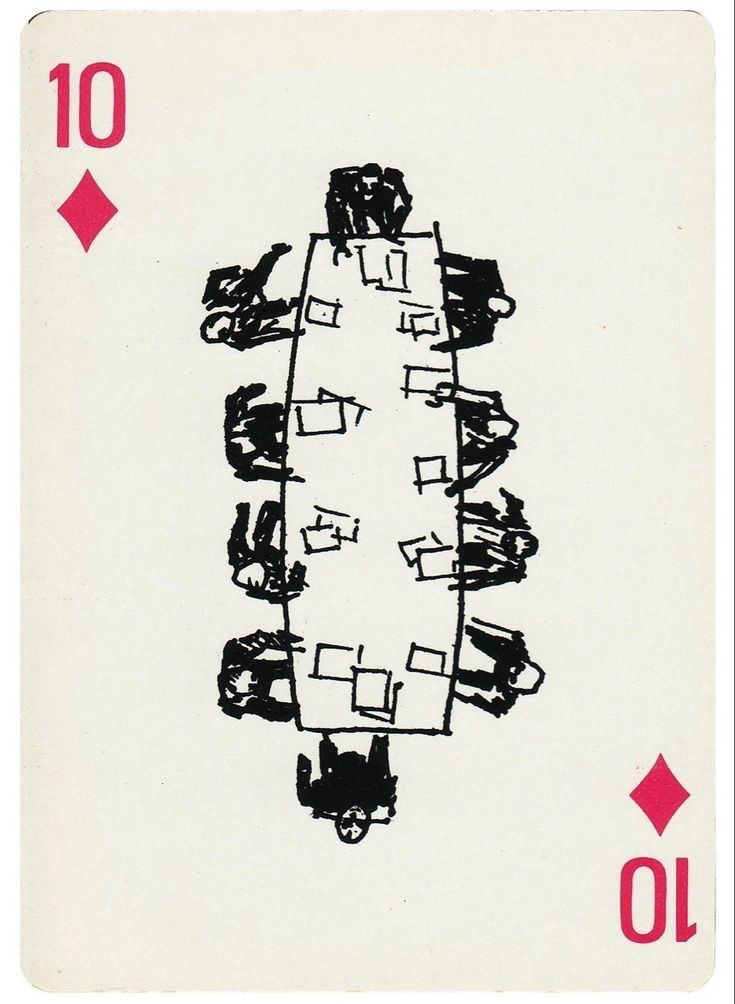

Michael LewisMichael Lewis's Liar's Poker is the most entertaining education you can get on how money, status, and incentives actually behave when the stakes are high. It reads like a fast, funny memoir, but underneath it is a sharp lesson on institutional culture—how smart people get pulled into games they don't fully understand, and start confusing winning with worth.

Michael Lewis's Liar's Poker is the most entertaining education you can get on how money, status, and incentives actually behave when the stakes are high. It reads like a fast, funny memoir, but underneath it is a sharp lesson on institutional culture—how smart people get pulled into games they don't fully understand, and start confusing winning with worth.

What I took from it isn't "finance lore," but a clearer lens on ambition: how environments shape your morals, your risk tolerance, and what you start calling "normal."

The Republic

PlatoPlato's Republic is the book I return to when I want my thinking to be sharpened, not comforted. It starts as a discussion about justice, but it quickly becomes an investigation into almost everything that shapes a life and a society—power, education, desire, ambition, truth, and the stories we tell ourselves to justify how we live.

Plato's Republic is the book I return to when I want my thinking to be sharpened, not comforted. It starts as a discussion about justice, but it quickly becomes an investigation into almost everything that shapes a life and a society—power, education, desire, ambition, truth, and the stories we tell ourselves to justify how we live. What makes it feel timeless is that it doesn't treat politics as a news cycle; it treats it as a mirror for human nature.

I read it as both a blueprint and a warning. The famous "ideal city" isn't just utopian theory—it's a stress test for values: if you tried to design a society around what is truly good, what would you have to cultivate in people, and what would you have to restrain? And the darker parts land just as hard: how easily societies slip into manipulation, how education can become propaganda, and how comfort can quietly replace wisdom. It's demanding, but incredibly practical—because it forces the question most of us avoid: what do you believe is good, and are you living as if it's true?

Inferno

Dante AlighieriDante's Inferno is one of the most vivid moral and psychological maps ever written. It's easy to describe it as "a journey through Hell," but what makes it stick is how recognizable it feels as a portrait of human patterns—pride that hardens into isolation, desire that turns into compulsion, anger that becomes identity.

Dante's Inferno is one of the most vivid moral and psychological maps ever written. It's easy to describe it as "a journey through Hell," but what makes it stick is how recognizable it feels as a portrait of human patterns—pride that hardens into isolation, desire that turns into compulsion, anger that becomes identity, betrayal that empties everything out. Each circle reads less like a supernatural threat and more like a metaphor for what happens when a certain kind of choice becomes a habit.

What I found most practical is Dante's sense of consequence. The punishments aren't random; they're almost "fitted" to the inner logic of the vice, like an external image of an internal state. That makes the book strangely clarifying: it forces you to ask what you're practicing every day, what you're excusing, and what direction those choices actually point in over a long time horizon. It's brutal, imaginative, and often beautiful—an old text that still feels like it understands modern psychology.

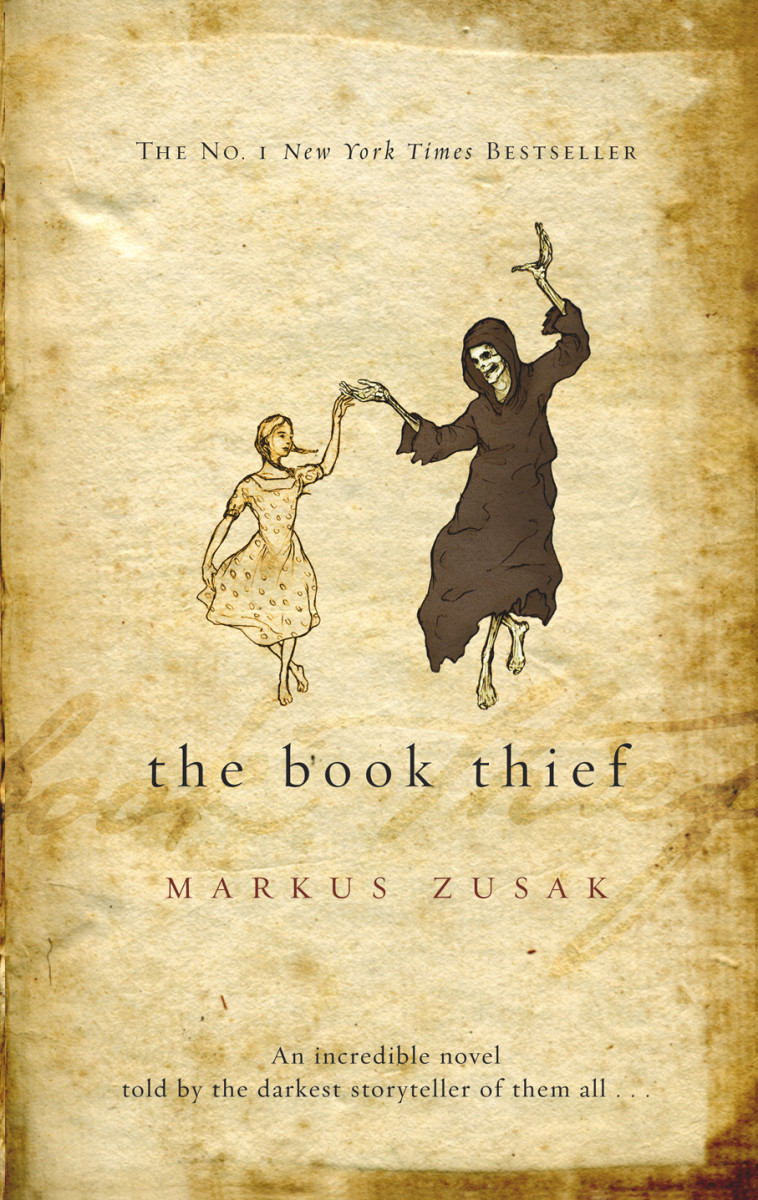

The Book Thief

Markus ZusakThe Book Thief made me feel, more than almost any novel, how words can be both shelter and weapon. Set in Nazi Germany and narrated by Death, it somehow manages to be heartbreaking and oddly luminous at the same time—because it's as much about ordinary tenderness as it is about catastrophe.

The Book Thief made me feel, more than almost any novel, how words can be both shelter and weapon. Set in Nazi Germany and narrated by Death, it somehow manages to be heartbreaking and oddly luminous at the same time—because it's as much about ordinary tenderness as it is about catastrophe. The story treats books as more than objects: they're stolen, shared, read aloud, clung to—like proof that a human life is still a human life, even when the world is trying to reduce people to nothing.

What stayed with me is the book's obsession with language: how propaganda can poison a society, and how a single honest sentence can keep someone alive inside themselves. It's devastating, but it also feels like a love letter to reading itself—the idea that stories don't just entertain us; sometimes they hide us, heal us, and help us endure.

Man's Search for Meaning

Viktor E. FranklMan's Search for Meaning is one of the most grounding books I've read—because it doesn't try to motivate you with optimism, it earns its insights at the highest cost. Frankl's core idea is both simple and demanding: meaning isn't something you stumble upon when life gets easy; it's something you choose and build, even when circumstances are unbearable.

Man's Search for Meaning is one of the most grounding books I've read—because it doesn't try to motivate you with optimism, it earns its insights at the highest cost. Frankl's core idea is both simple and demanding: meaning isn't something you stumble upon when life gets easy; it's something you choose and build, even when circumstances are unbearable. The book reframes suffering without romanticizing it, and that balance is what makes it feel honest.

What stayed with me most is the way Frankl separates what happens to you from what you do with it. Even when your options are stripped down to almost nothing, there's still a final kind of freedom: the stance you take, the values you refuse to betray, the purpose you hold onto. I come back to this book whenever I feel scattered or overly absorbed by short-term stress—it's a sharp reminder that a good life isn't just comfort or achievement, but direction.

The Stranger

Albert CamusThe Stranger is the book I point to when people reduce Camus to "existential gloom." I think Camus should be fully understood—not in a pessimistic, downer way, but in the true philosophical sense of the absurd: the tension between our hunger for meaning and the world's indifference to providing it. The novel's flatness isn't emptiness; it's a deliberate mirror held up to how we judge, narrate, and moralize people into acceptable stories.

The Stranger is the book I point to when people reduce Camus to "existential gloom." I think Camus should be fully understood—not in a pessimistic, downer way, but in the true philosophical sense of the absurd: the tension between our hunger for meaning and the world's indifference to providing it. The novel's flatness isn't emptiness; it's a deliberate mirror held up to how we judge, narrate, and moralize people into acceptable stories.

What hit me is that Meursault isn't condemned only for what he does, but for what he doesn't perform: the expected emotions, the socially approved grief, the right words at the right time. And that's where Camus becomes practical. He forces the question: how much of "being good" is real ethics, and how much is just fitting the script? The Stranger is unsettling, yes—but it's also clarifying. It's a stripped-down lesson in honesty, conformity, and what it means to face life as it is, without illusions, and still choose how to live.

The Poems of Robert Browning

Robert BrowningRobert Browning's poems feel like stepping into a mind mid-thought—dramatic, intense, and strangely modern in how psychologically sharp they are. What I love is that he doesn't write "pretty" poems as much as he writes voices: people justifying themselves, revealing themselves, contradicting themselves.

Robert Browning's poems feel like stepping into a mind mid-thought—dramatic, intense, and strangely modern in how psychologically sharp they are. What I love is that he doesn't write "pretty" poems as much as he writes voices: people justifying themselves, revealing themselves, contradicting themselves. You don't just read a scene—you're trapped inside someone's logic, and you start noticing how easily intelligence can become self-deception, or how a single obsession can bend an entire life.

Browning is also one of my favorite reminders that poetry can be a form of moral inquiry. So many of his pieces feel like miniature case studies in ambition, pride, desire, guilt, and love—told with rhythm and wit, not lectures. Each time I return, I catch a new layer: a hidden motive, a quiet irony, a line that hits harder because I've lived a bit more since the last read.

A Gentleman in Moscow

Amor TowlesA Gentleman in Moscow is one of the most charming reminders I know that a life can be made large even when the world makes it small. On paper, it's about confinement—a Count sentenced to live out his days inside a grand hotel—but the book becomes the opposite of claustrophobic. It's a story about style as a moral choice: dignity without arrogance, taste without snobbery, discipline without coldness.

A Gentleman in Moscow is one of the most charming reminders I know that a life can be made large even when the world makes it small. On paper, it's about confinement—a Count sentenced to live out his days inside a grand hotel—but the book becomes the opposite of claustrophobic. It's a story about style as a moral choice: dignity without arrogance, taste without snobbery, discipline without coldness. Towles makes "character" feel like something you can practice.

What I loved most is how the novel treats attention as a kind of power. The Count notices people, learns them, and elevates the everyday into ritual—meals, friendships, conversation, small acts of loyalty. It's funny and warm, but never shallow; underneath the elegance is a quiet insistence that your circumstances don't get to dictate your spirit. Every time I think about building a good life, this book comes back to me: you don't need limitless freedom—you need depth, craft, and the courage to meet the day with grace.

All the Beauty in the World

Patrick BringleyThis book was given to me as a gift, and since The Met has a special kind of place in my heart, this book has a special kind of place here. All the Beauty in the World is quiet, tender, and deeply human—a memoir told from the perspective of a Met guard who spends his days standing beside masterpieces, watching both the art and the people who come to meet it.

This book was given to me as a gift, and since The Met has a special kind of place in my heart, this book has a special kind of place here. All the Beauty in the World is quiet, tender, and deeply human—a memoir told from the perspective of a Met guard who spends his days standing beside masterpieces, watching both the art and the people who come to meet it.

What I love about it is how it reframes museums as something more than "culture" or "tourism." The Met becomes a shelter, a teacher, and a kind of daily ritual—proof that beauty isn't just decoration, it's nourishment. Bringley writes with a calm clarity that makes you slow down: to notice details, to sit with grief without rushing it, and to let art do what it's always done at its best—give shape to feelings you couldn't name before. Every chapter feels like a reminder that attention is a form of reverence, and that a life can be steadily rebuilt through small, repeated encounters with beauty.

The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse

Charlie MackesyI remember feeling out of this world when I finished this book. I believe that books that make you feel fantastical deserve to be praised—so here it is: a toast to Charlie Mackesy. The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse is tender in a way that doesn't feel childish; it's gentle, but it lands with the weight of something true.

I remember feeling out of this world when I finished this book. I believe that books that make you feel fantastical deserve to be praised—so here it is: a toast to Charlie Mackesy. The Boy, the Mole, the Fox and the Horse is tender in a way that doesn't feel childish; it's gentle, but it lands with the weight of something true. It reads like a warm conversation you didn't know you needed, stitched together with drawings that somehow say as much as the words.

What I love most is how it treats kindness as strength and vulnerability as courage. It doesn't argue or lecture—it just offers small lines that open big doors: about friendship, self-worth, asking for help, and continuing even when you're afraid. It's one of those books you can finish in an hour, then carry for months—because the best parts keep echoing long after the last page.

The Double

Fyodor DostoyevskyThe Double feels like a psychological nightmare written with surgical precision. On the surface it's the story of a timid civil servant whose life begins to unravel when a man identical to him appears—but the genius is that you're never allowed to treat it as a simple plot twist. It reads like an exteriorization of an inner collapse: insecurity, paranoia, and the hunger for recognition taking on a life of their own.

The Double feels like a psychological nightmare written with surgical precision. On the surface it's the story of a timid civil servant whose life begins to unravel when a man identical to him appears—but the genius is that you're never allowed to treat it as a simple plot twist. It reads like an exteriorization of an inner collapse: insecurity, paranoia, and the hunger for recognition taking on a life of their own.

What I took from it is how brutally Dostoyevsky understands self-image. The "double" isn't just a person—it's the version of you that you fear, envy, or secretly want to be: smoother, bolder, more socially fluent, more admired. And once that comparison starts, it's corrosive. The book becomes a study of how shame distorts reality, how status anxiety turns ordinary interactions into threats, and how quickly a mind can start arguing with itself. It's dark, tense, and oddly modern—like he wrote it for anyone who's ever felt split between who they are and who they're trying to perform.

The Alchemist

Paulo CoelhoThe Alchemist is where my reading passion started. It's simple on purpose—almost fable-like—and that simplicity is exactly what makes it powerful: it speaks straight to the part of you that still believes your life can be guided by meaning, not just momentum. Every time I return to it, I'm reminded that "finding your path" isn't a single dramatic breakthrough—it's a series of small acts of courage, attention, and trust.

The Alchemist is where my reading passion started. It's simple on purpose—almost fable-like—and that simplicity is exactly what makes it powerful: it speaks straight to the part of you that still believes your life can be guided by meaning, not just momentum. Every time I return to it, I'm reminded that "finding your path" isn't a single dramatic breakthrough—it's a series of small acts of courage, attention, and trust.

What I took from it early on, and still take from it now, is the idea that desire can be sacred when it's honest. The book reframes fear as the real antagonist—not failure, not difficulty, but the quiet voice that convinces you to stay safe and small. It's a story about listening, taking the leap, and learning that the treasure isn't only at the destination—it's in the person you become by refusing to ignore the calling.

The Picture of Dorian Gray

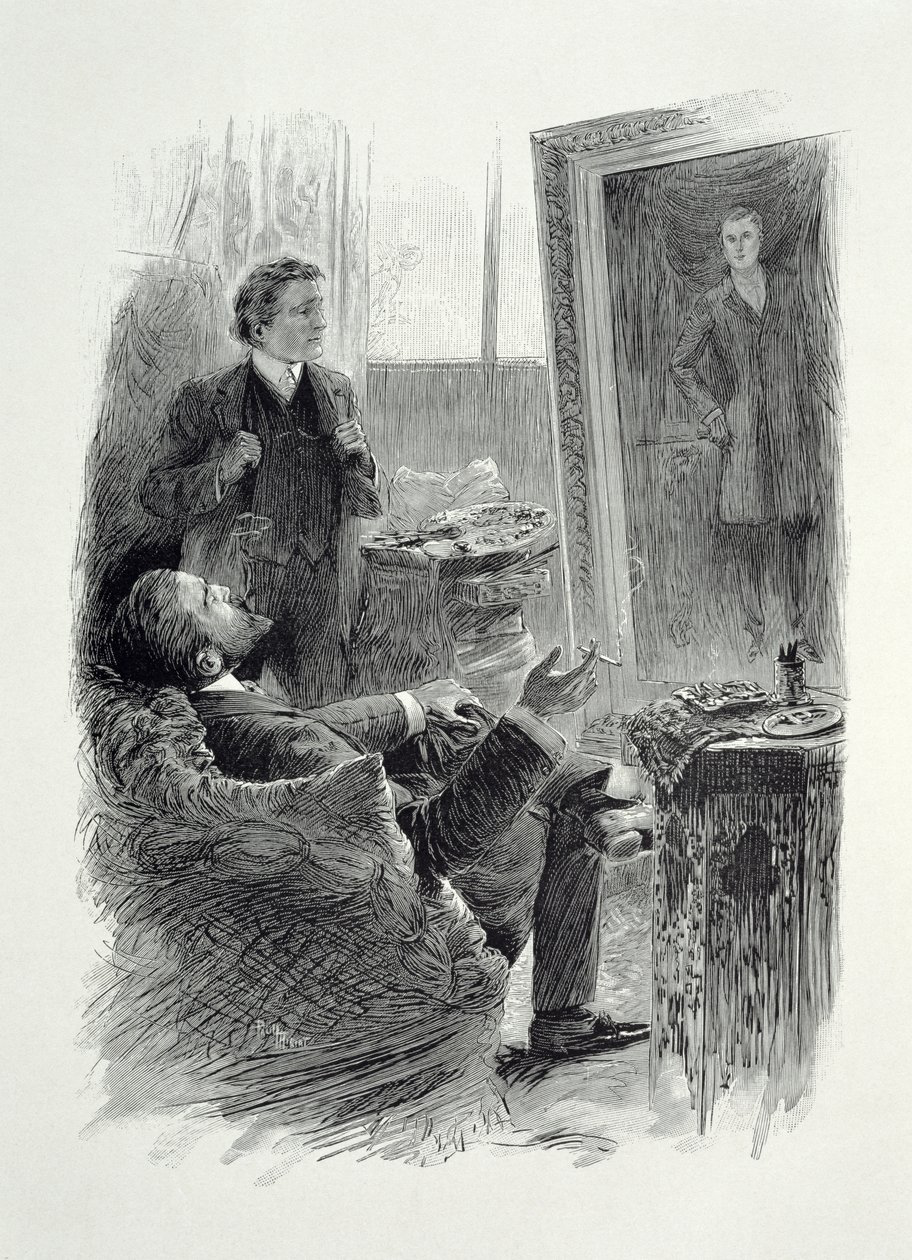

Oscar WildeThe Picture of Dorian Gray feels complete to me—like Wilde somehow wrote the definitive story of Dorian Gray, so perfectly that nothing else can come close to Dorian Gray when it comes to Dorian Gray. It's witty, seductive, and poisonous in the most deliberate way: a beautiful surface with rot underneath, written by someone who understands exactly how charm can become a weapon.

The Picture of Dorian Gray feels complete to me—like Wilde somehow wrote the definitive story of Dorian Gray, so perfectly that nothing else can come close to Dorian Gray when it comes to Dorian Gray. It's witty, seductive, and poisonous in the most deliberate way: a beautiful surface with rot underneath, written by someone who understands exactly how charm can become a weapon.

What I love is how the book turns vanity into philosophy. It isn't just "a moral tale" about beauty and corruption—it's an anatomy of influence: how a few ideas, repeated at the right moment by the right person, can rewire someone's soul. The horror is psychological before it's supernatural: the slow trade of conscience for pleasure, of integrity for image, until the self becomes performance. Wilde makes it feel glamorous right up until it doesn't—and that's the genius.